Recently I’ve been listening to Invisibilia, a podcast “about about the unseen forces that control human behavior – our ideas, beliefs, assumptions, and thoughts.” This week’s episode is on Frames of Reference. The first segment is about Kim, a doctor with autism. Kim participated in a study designed to determine whether stimulating specific regions of her brain with strong magnetic impulses (transcranial magnetic stimulation or TMS) would change her ability to understand some of the subtleties of language — sarcasm and emotional content, in particular.

TMS did change her abilities, but only for an hour or so. And in that hour, Kim was given a window into an entire world that she had known nothing about prior to participating in the study. In one part of the story, Kim described an experiment in which she watched a video clip before they administered the TMS, and again after the TMS. She describes the video from her perspective each time — first as an autistic person hearing the words and being confused, and then immediately after the TMS when she could understand that the intention of the speaker directly contradicted her words. “And now I saw it: the body expression, the facial expression, and the tone of voice in that interaction. I completely missed the meaning of the whole interaction until after the TMS. And then I saw the whole thing clearly.”

I think that this may be the first time I have truly (TRULY) understood how difficult it is for autistic people to understand the social-emotional world. And how utterly effortless it is for others.

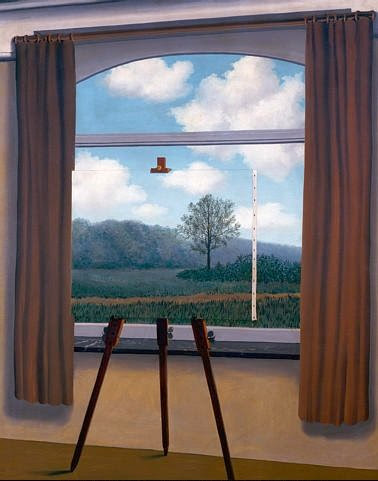

René Magritte – The Human Condition – 1933

At the end of the segment, the hosts (Alix Spiegel and Hanna Rosin) discuss whether they would want to get the treatment if they had autism. Hanna answers, “If it were me, I think I would make the same choice Kim made. But if it was someone I loved, a child of mine, my first instinct would be to protect them from it… Because another thing we value is self-acceptance. You don’t want someone spending their whole life grasping for an ideal version of themselves, and not the person who they are.” Alix then says, “I think that for Kim, seeing this other world, getting this other frame of reference… gave her self-awareness, and the grace of self-awareness. She was suddenly able to see clearly what she was, and what she wasn’t.”

I was listening to this episode with my oldest son, who shares Kim’s diagnosis. After the segment finished, I paused the podcast and asked him what he thought. He answered that he didn’t think he would want to get the treatment. I asked him why not. He said that he was okay with the way he processes the social world.

I then asked him about the video clips and what he would have heard. He said that while he would have noticed the nuances of the interaction (the body language, the facial expressions, the tone), he would have focused on her words and been confused.

And then he shared two more insights. The first was about how he thought understanding people was like programming computers. He said that Kim’s experience of the video conversation was like when he wrote a program and thought it would work perfectly, and then when he tried to compile the code or run the program, it worked differently than he’d thought it would. This led him to look at the code carefully, and try again. And, inevitably, it would fail again, but in a different way. So he would try another fix, and another, and another, until he was able to get it right. He does the same thing when talking to others. Communication by successive approximation!

The second was about a book he had just read, Moral Politics – How Liberals and Conservatives Think, by George Lakoff. The most important lesson my son took from that book was that you can understand people if you can understand their frame of reference. When he first read the book, his frame of reference was that of a liberal. When viewing our political system through that framework, he was unable to understand why conservatives felt as they did about certain issues. After reading Lakoff’s book, he understood that conservatives have a different frame of reference. It is not a bad frame, just a different frame. Prior to reading Moral Politics, he had no idea that he was biased in his perceptions. That’s true of everyone, he said. We all have our own frame of reference, shaped by our unique neurobiology and also by our experiences.

As he spoke, I began to more clearly appreciate the fact that none of us can ever truly understand each other, just as we can never truly understand ourselves.

We can just make successive approximations until we understand each other well enough.

Do you need help with your child? Sarah Wayland can help you figure out how to support your child via classes, Special Needs Care Navigation services, Parent Coaching, or as your certified Relationship Development Intervention (RDI) consultant.

I love this blog post! Your son sounds like a wise and thoughtful person.

You are amazing. Thank you so much for sharing this!

I’m so glad you enjoyed it, Eva. My son is a truly amazing human being. Brave, wise, and caring. I’m so glad to be able to share a bit of him with the world!

Thanks for this blog. Your son’s ability to express what is like to have ASD, is extremely valuable.

Sarah, I’m studying Clean Language and its careful “successive approximation” via metaphor. We could all benefit from your son’s perspective on programming and communication–stop making assumptions and stay until it works.

Thanks for sharing, Sarah!